“There is no real development without integrity, that is- a love of truth.” Frank Lloyd Wright

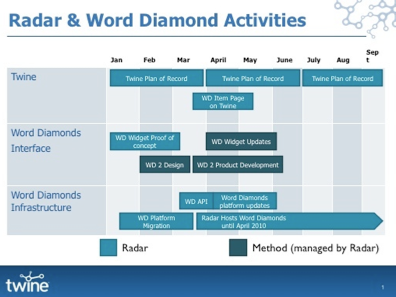

RADAR NETWORKS, INC., Debtor. Case No. 11-33990 Chapter 7 Date: Time: Place: Judge: June 8, 2012 9:30 a.m. Courtroom 23 235 Pine Street, 23rd Floor San Francisco, CA Hon. Thomas E. Carlson DECLARATION OF EVAN MANDEL IN SUPPORT OF REPLY TO OPPOSITION TO MOTION TO DISMISS I, Evan Mandel, declare:

1. I am an attorney licensed to practice law in the State of New York, and am a principal of the law firm of Mandel Bhandari LLP, counsel for Kate Paley (“Paley”), a creditor herein, in connection with her lawsuit pending in the San Mateo County Superior Court, San Mateo County Superior Court, Case N. CIV 494701 (the “State Court Action”) against Radar Networks, the debtor herein (“Radar” or the “Debtor”), its directors, Ross Levinsohn, Steve Hall, and Noah Spivack (“Insiders” or “Defendants”), and Evri, Inc. (“Evri”) for fraud, fraudulent conveyance, breach of contract, breach of fiduciary duty, declaratory judgment, conversion and constructive trust. In such capacity, I am personally familiar with each of the facts stated herein, to which I could competently testify if called upon to do so in a court of law.

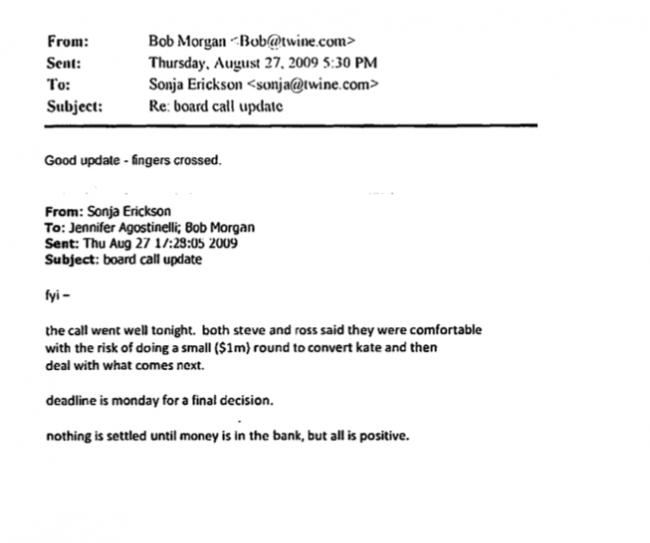

2. In connection with the State Court Action, the following facts and evidence were obtained in the course of discovery: a. Paley’s $3 million loan, plus interest, was payable on demand by Paley any time on or after September 30, 2009, unless new funding of $4 million was received by the Debtor, in which case the note would be automatically converted. See, Exhibit C to Declaration of Noah Spivack filed in support of the Debtor’s Opposition (“Spivack Decl.”).

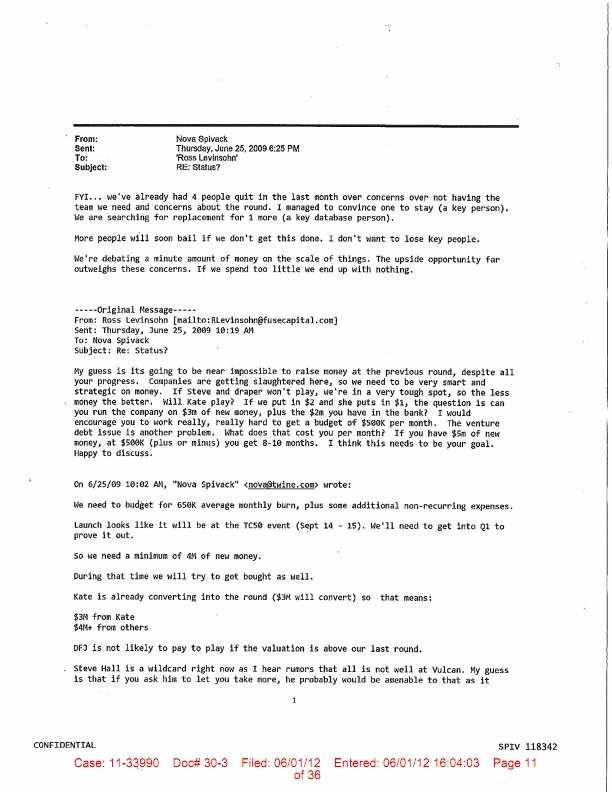

As of September 30, 2009, Radar had at least $1,002,557 cash on hand and an estimated value of $20,000,000. See Exhibit A (Financial Statement Compilation for the Nine Months Ended September 30, 2009). b. On June 25, 2009, Spivack wrote to Levinsohn explaining that “we need a minimum of 4M of new money,” which would result in “$3M from Kate [and] $4M+ from others.” See Exhibit B (June 25, 2009 email). The next day, Spivack explained further: “One wrinkle is that Kate’s note is due on 9/30/09. On that date, if she has not converted yet, she can request repayment. That would of course be bad. So we actually should convert her.” See Exhibit C (June 26, 2009 email). c. For several weeks, Hall tried to convince Paley to voluntarily relinquish her right to get repaid on September 30, however, she refused. Radar sent Paley a document purporting to be a release and an extension of the maturity date of her loan, however, Paley did not sign it.

d. On September 15, 2009, Levinsohn’s company, Fuse, and Hall’s company, Vulcan,[each investing exactly half of] $842,192.42 and the Directors purported to convert Paley’s $3 million loan to equity. The State Court found that the conversion was improper.

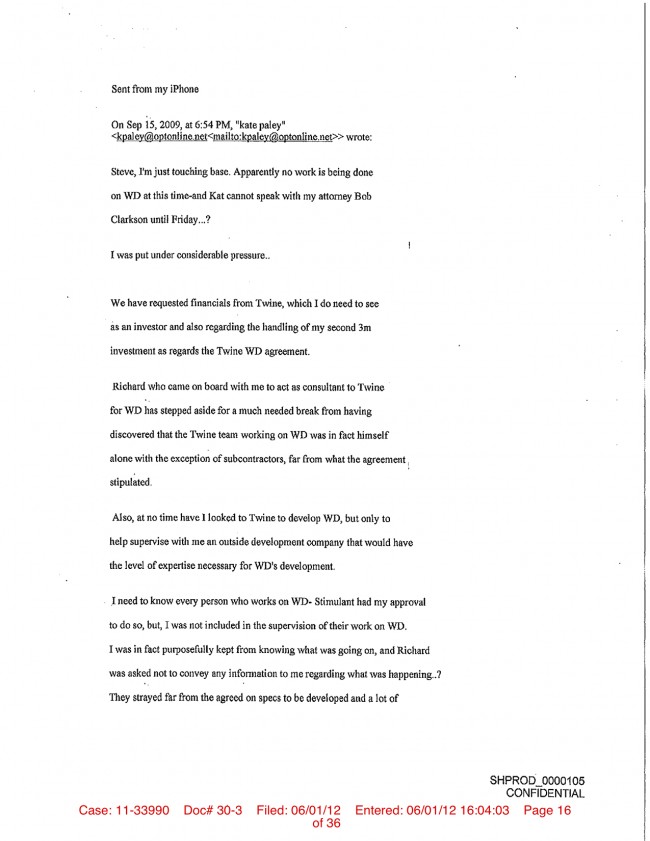

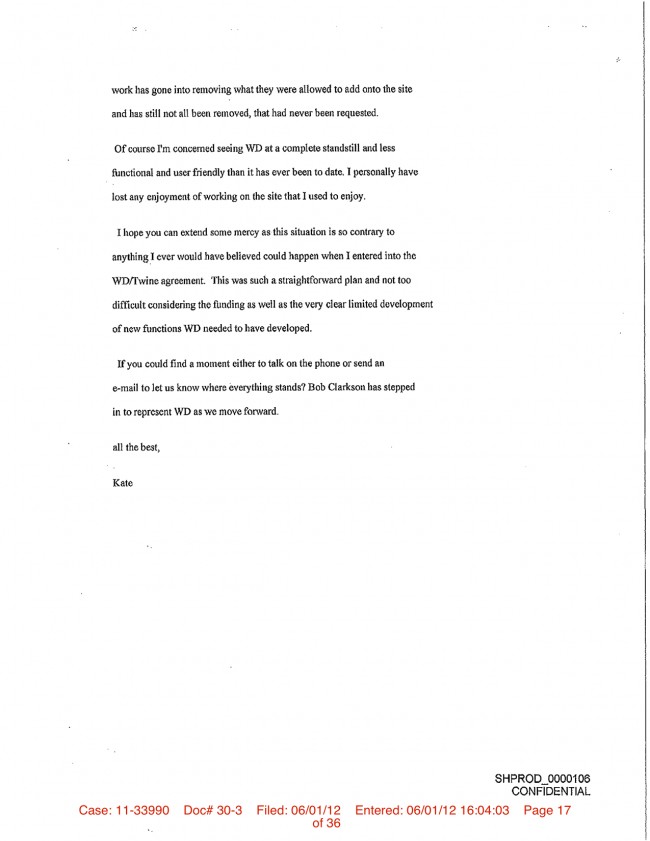

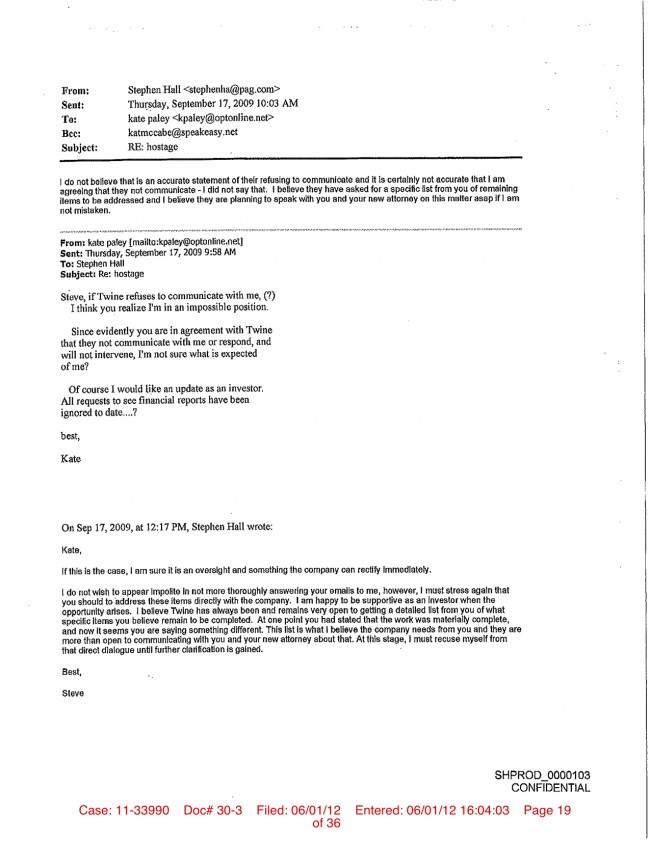

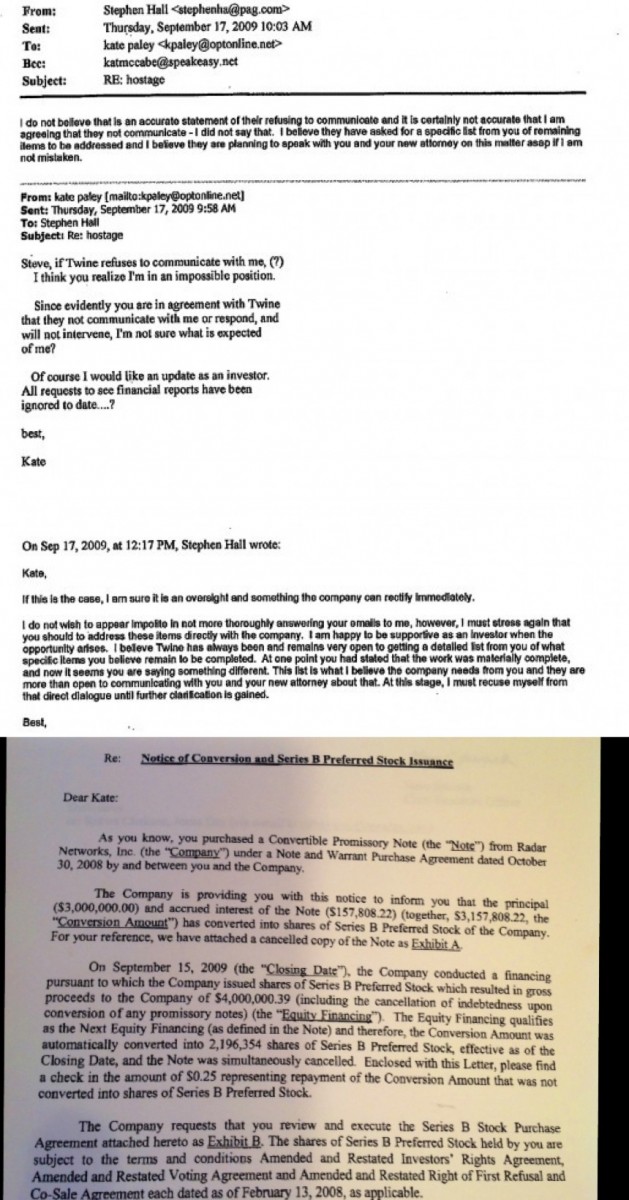

e. On September 15, 2009, before she knew about the conversion, Paley wrote to Hall, whom she thought she could trust. She implored him to help her work things out with her investment and Word Diamonds. Paley asked Hall to help her communicate with Radar because “I do need to see [Radar’s Financials] as an investor and also regarding the handling of my second 3m investment as regards the Twine [] agreement.” Insidiously, the next day, Hall replied, “I am sure it is an oversight and something the company can rectify immediately.” See Exhibit D (September 15, 2009 email).

Hall did not tell Paley that he had just implemented the scheme to convert Paley’s $3 million loan to equity. See Exhibit E (September 17, 2009 response from Hall).

f. In March 2010, all of the Debtor’s assets were sold to Evri for approximately $1,125,000 in cash, plus shares in Evri representing a 3% – 5% stake in Evri. The sale to Evri was made despite a February 2010 offer by Intellectual Ventures to pay $2.75 million for Radar’s patents alone, plus a non-exclusive license to Radar to use the patents. g. On July 26, 2009, Hall introduced Radar’s CEO Spivack to Evri CEO Hunsinger, and Spivack immediately recognized the introduction for what it was: “I bet Steve Hall is plotting to acquire our assets at firesale price into Evri.” See Exhibit F. And that is precisely what Hall was plotting, and it is exactly what he did.

Hall used confidential information about Radar’s business that he acquired as director and fiduciary of Radar to assist Evri in acquiring Radar’s assets at a price that was far below their fair market value. Spivack valued Radar’s assets as being “worth more than $20 million” in November 2009. See Exhibit G. h. In March 2010, Radar’s assets were sold to Evri for $1,125,000 in cash and 1,746,016 in Evri restricted shares. Depending on the valuation of Evri’s restricted shares, Evri was able to purchase substantially all of Radar’s assets for approximately $1,125,000.1

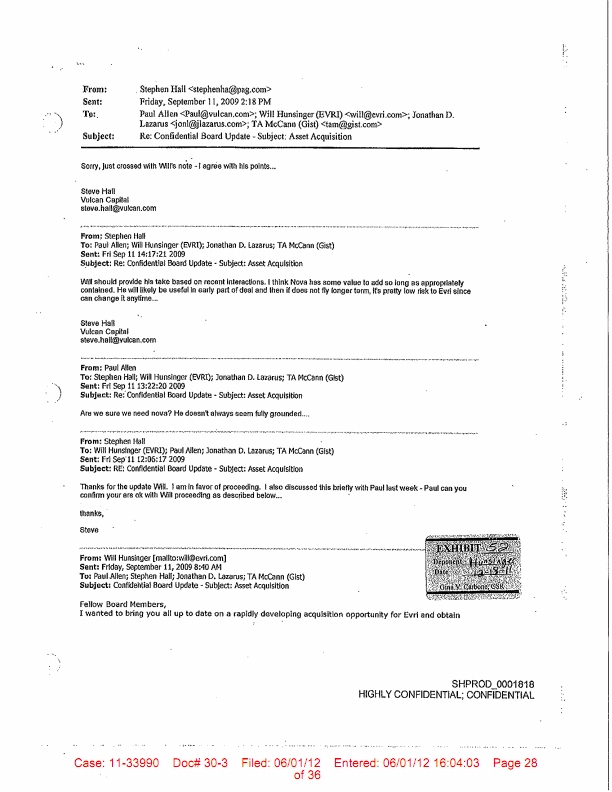

i. In seeking approval from the Evri Board of Directors to enter into negotiations to purchase Radar’s assets, Hunsinger explained that Hall had provided his insider’s perspective: Working closely with Steve H to come to this conclusion, I strongly believe that Evri has an opportunity to acquire valuable assets and talent from Radar Networks on very attractive terms. . . . Given the target companies[‘] situation, Evri has significant leverage and we are uniquely positioned to execute a clean, pure equity deal obtaining significant option value on assets for a relatively low price.”

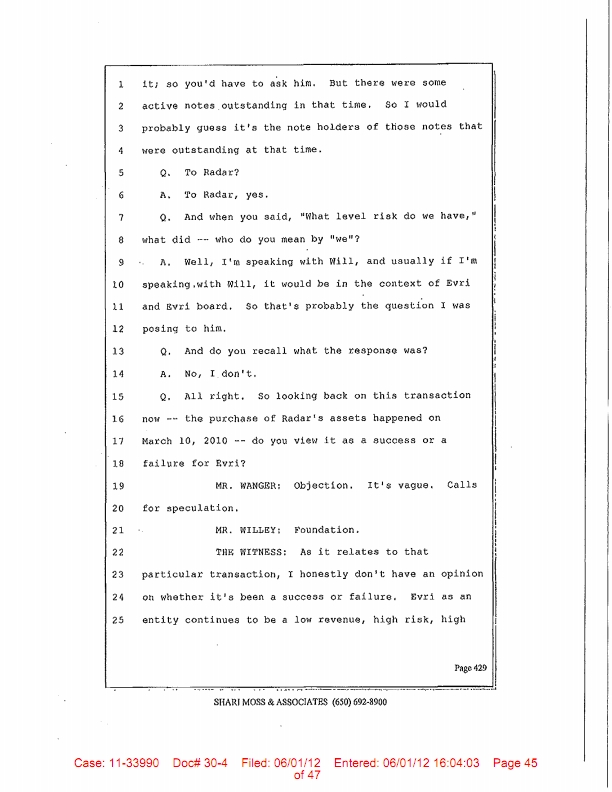

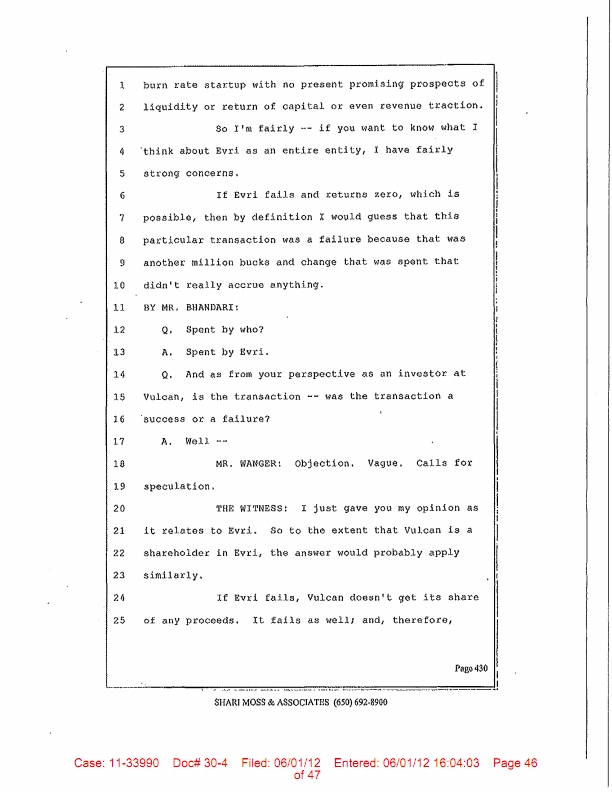

1 Defendant Levinsohn claims that his investment fund is “carrying [the Evri shares] at zero” but “to this day, it’s unclear what the total amount of consideration [Levinsohn’s investment fund] received as part of the purchase agreement for Radar’s assets is.” Exhibit Y (Levinsohn Deposition Transcript, 259:2-17.) .

Exhibit H. Hall also provided Hunsinger with Radar’s confidential information as to whether Evri could poach Radar engineers. Exhibit I. j. Obtaining Radar’s assets at a firesale price was not Hall’s only motive for wanting to drive Radar out of business. The Vulcan entity that had invested in Radar, Vulcan II, had realized a significant amount of taxable income, and Radar’s bankruptcy would permit Vulcan II to realize a total tax loss of its Radar investment. See Exhibit J (“[F]or months [Hall] has been saying Vulcan could use the write off, and now he’s happy to have the company shut down and take the write-off.”)) k. Indeed, in numerous private communications, Spivack and his COO accused Hall of (1) “letting [Radar] fall apart” so that Vulcan (or Evri) could “tak[e] over the assets” (Exhibit K); (2) having a plan to facilitate Evri’s acquisition of Radar at a “firesale price” (Exhibit L); (3) wanting to “drive [Radar] into bankruptcy and take our assets” (Exhibit M); (4) intentionally “starv[ing] [Radar], forc[ing] layoffs, and then corner[ing] us and forc[ing] a sale to Evri” (Exhibit M); and (5) Hall “wants us to fails so that Evri can get us in a wind down” (Exhibit N).

l. The sale to Evri enabled Hall to increase his ownership interest in Radar’s assets, obtain a tax advantage and reputational benefits.

In 2006, Vulcan made its first investment in Radar. Hall holds a carried interest in the Vulcan investment fund that owned an equity position in Radar and a contractual right to receive profits generated by the fund. At the time of the transfer of Radar’s assets to Evri, Evri was, and still is, in effect a subsidiary of Vulcan. Vulcan has invested at least $36 million in Evri. Vulcan owns more than 90% of the issued and outstanding capital stock of Evri and Paul Allen controls Vulcan.

In deposition, Hall freely acknowledged that Vulcan controlled Evri. Hall has personally invested in the Vulcan entity that manages Evri. (Exhibit O) (Vulcan Capital Venture Capital II LLC (“Venture II”) owns Evri; Venture II is managed by Vulcan Capital Venture Capital Management II LLC (“Management II”)). Hall has invested money in Management II. m. Hall received substantial benefits from Radar’s sale of its assets to Evri. As a director and indirect owner of Evri, as a result of the asset sale, Hall obtained control of all of Radar’s assets and a greater ownership interest in such assets through his interest in Evri.

Hall also received a major tax advantage from the asset sale: the Vulcan fund that owned Radar had realized approximately $85 million in taxable income as a result of at least one extremely successful investment; the dissolution of Radar that followed the asset sale allowed Vulcan to realize the tax loss that it suffered in its Radar investment; and that loss became a valuable deduction for the owners of the Vulcan fund that owned Radar. (Exhibit O) (Hall Dep. at 258:2-259:25.)

In fact, Hall repeatedly told Spivack and other Radar personnel that he wanted Radar to go bankrupt so that he and Vulcan could obtain the associated tax benefits. (Exhibit J). n. Radar’s assets were worth significantly more than $1.125 million, based on the February 2010 offer from Intellectual Ventures to pay $2.75 million for Radar’s patents, Spivack’s valuation of Radar at approximately $45 million to $50 million as of the fall of 2009 (Exhibit P); and Exhibit Q (“45M+ is reasonable”), and Vulcan’s willingness to pay more for Radar’s assets

(Exhibit R) (Hall email to Paul Allen, the head of Vulcan that, at the time of the Intellectual Ventures offer, Vulcan was willing to pay more: “So we are in the middle of playing some hardball maneuvering to get this over the goal line without having to pay any more money for it.”); and Radar’s potential claim against Evri for violating Radar’s patents (Exhibit S (“[T]here is a potential lawsuit here. A big one, I think.”), (“They are violating many of our patents.”).)

o. Levinsohn’s sworn testimony in the State Court litigation is that anything that benefited Fuse’s ComVentures VI fund also benefited him personally. Also, Levinson’s “personal money” was at stake “in our fund,” i.e. ComVentures VI. p. ComVentures loaned Radar $271,000 on November 30, 2009 and was one of Radar’s unsecured creditors. The Levinsohn Fund was also promised additional shares in Evri several months after the transaction for Radar’s assets closed.

Indeed, The Levinsohn Fund received 381,595 “excess shares” of Evri’s common stock from the Asset Sale in June 2010, and 571,770 shares of Evri common stock in June 2011. Exhibit T (Corrected Levinsohn Decl. ¶31.)

This additional payment to Levinsohn’s investment fund was not disclosed in the March 2010 Asset Purchase Agreement.

Levinsohn also received a reputational benefit by orchestrating a pay-out to his investment fund and achieving a “soft landing” for his investment. Levinsohn was responsible for the loan being made and, as a result, was “out on a limb with [his] firm.” Exhibit U.

q. As for Spivack, he knew that unless Radar commanded a sale price in excess of $63 million, he and his management team would not be able to cash in their shares at all. See Exhibit V (“The preferred shareholders have up to $63 mm of liquidation preferences from the A and B rounds in place.”) In that same email, Spivack explains that even if the sale price to Microsoft (rather than Evri) is somewhere in the range of $40 million, unless the deal comes with a “management carve out” he and the other common stock holders will “get[] nothing.”

Faced with the prospect of Radar’s investors making millions of dollars on their investments with Spivack “getting nothing” or Spivack making some money and the investors getting nothing, Spivack chose the latter option.

In negotiations with Evri, Spivack’s primary concern was not maximizing shareholder value – it was fluffing his own golden parachute. In a November 4, 2009 email, Spivack told Hall that the main financial goal for “other investors” is to offer them just enough value to “get their votes and avoid liability issues.” But for himself, he was very specific: (i) a salary of $250,000; (ii) a six month severance package; (iii) 10% of equity in Evri with “some of it already vested at signing”; (iv) if less equity, then a higher salary; (v) a seat on the Evri board; and (vi) “to be able to monetize some of my Radar equity now, at the time of sale, to cash.” When Evri closed the deal, it offered him a salary of approximately $250,000/year, Spivack served as a consultant for approximately six months, and he was given a substantial amount of equity in Evri. Spivack believed this was payment for “keeping my mouth shut about what they did to us.” Exhibit W. The deal also included a payment to Lucid Ventures, Inc., which is an investment vehicle owned and operated by Nova Spivack. I declare under penalty of perjury that the foregoing is true and correct, and that this declaration was executed on June 1, 2012 at New York, New York. _________________________________ Evan Mandel -7- Case: 11-33990 Doc# 30-2 Filed: 06/01/12 Entered: 06/01/12 16:04:03 Page 7 of 10777/MANDEL AFF. V.5 7

Fontain De La Tour

Fontain De La Tour

.

.

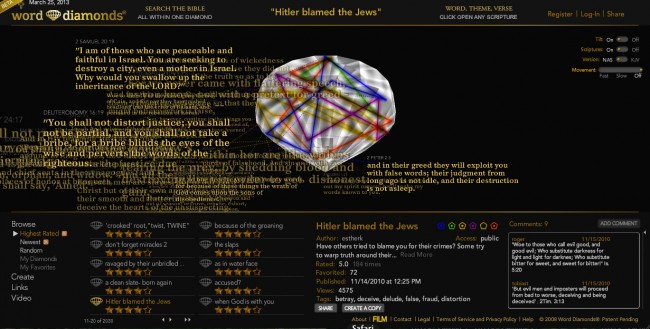

Mr. Hall, whose jujitsu legal tactics continue to manufacture, out of whole cloth, scenarios to obscure his fraudulent scheme to defraud Kate Paley and Worddiamonds, now wants to teach us how to proceed- not in truth, but in tactics?

Mr. Hall, whose jujitsu legal tactics continue to manufacture, out of whole cloth, scenarios to obscure his fraudulent scheme to defraud Kate Paley and Worddiamonds, now wants to teach us how to proceed- not in truth, but in tactics?

Bible Resource Center

Bible Resource Center